Last Dance: Aunt Jenny, Uncle Vincent, and AIDS—PLUS—In Remembrance, Elton John's "Empty Garden (Hey Hey Johnny)" as Sung by My Charlie.

In 1989, days before her 37th b'day, Jenny rose to cue Marvin's "Inner-City Blues"—a final dance with her mother, sister, and son. Her brother Vincent had died six months earlier. This is their story.

If you are viewing this via e-mail, then please do CLICK THE HEADLINE TITLE ABOVE to access online the MOST UP-TO-DATE and CORRECTED VERSION

As her body withered away,

her spirit accepted her God

with maddening abandon.

At her wake,

Aunt Jenny would leave her children

praying for more time.

Last Dance: Uncle Vincent, Aunt Jenny, and AIDS

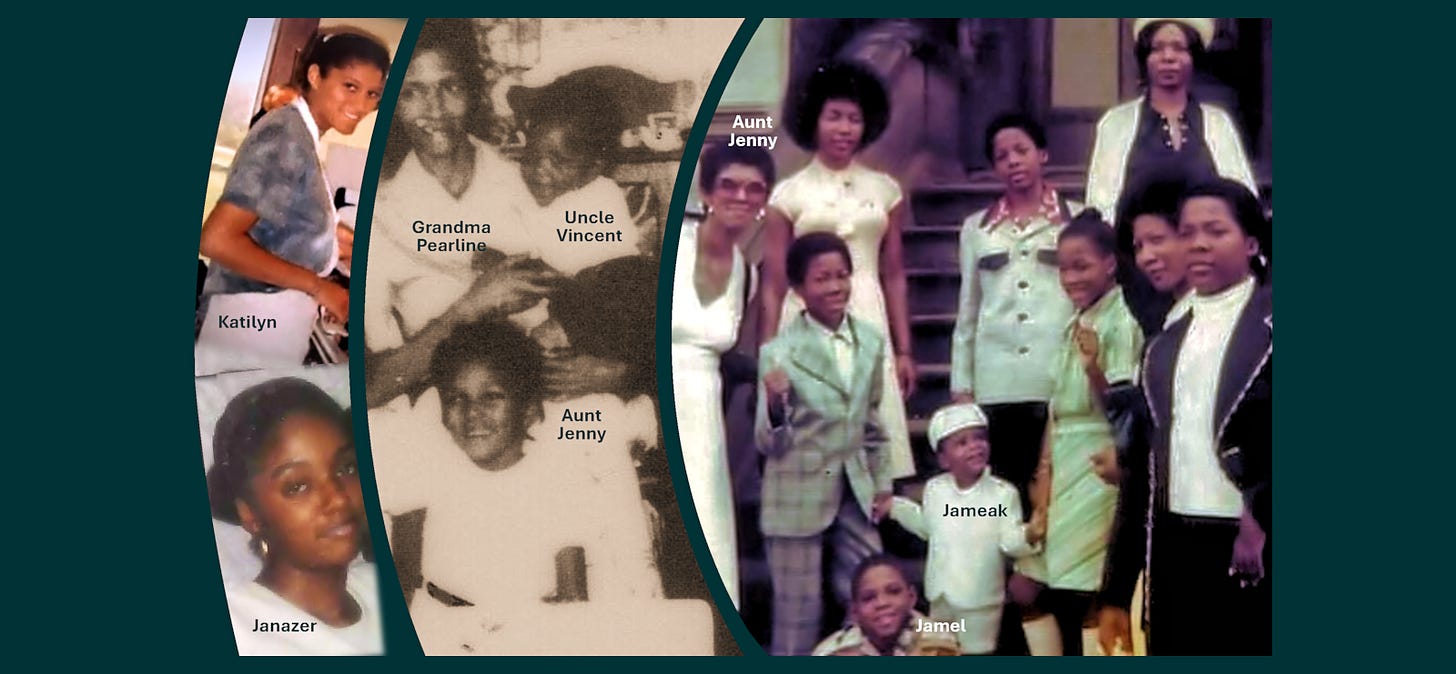

Uncle Vincent and His Children

In the spring of 1989, my uncle, Vincent Lee, not yet 35 years old, died of AIDS. He was a man I remember for his love of music, especially The Temptations.

He was also a protector and acted as my surrogate father when my own father was not around.

His love for his music and for me stays with me to this day.

He fell for one Beverlyn Brown who would become his common-law wife.

Two children survive Uncle Vincent and Aunt Beverlyn—a son, Vincent Brown (aka “Little” Vincent), and LaShette Rice (a stepdaughter to Uncle Vincent) who was Beverlyn’s second child.

LaShette is a mother of three children, two boys and a girl.

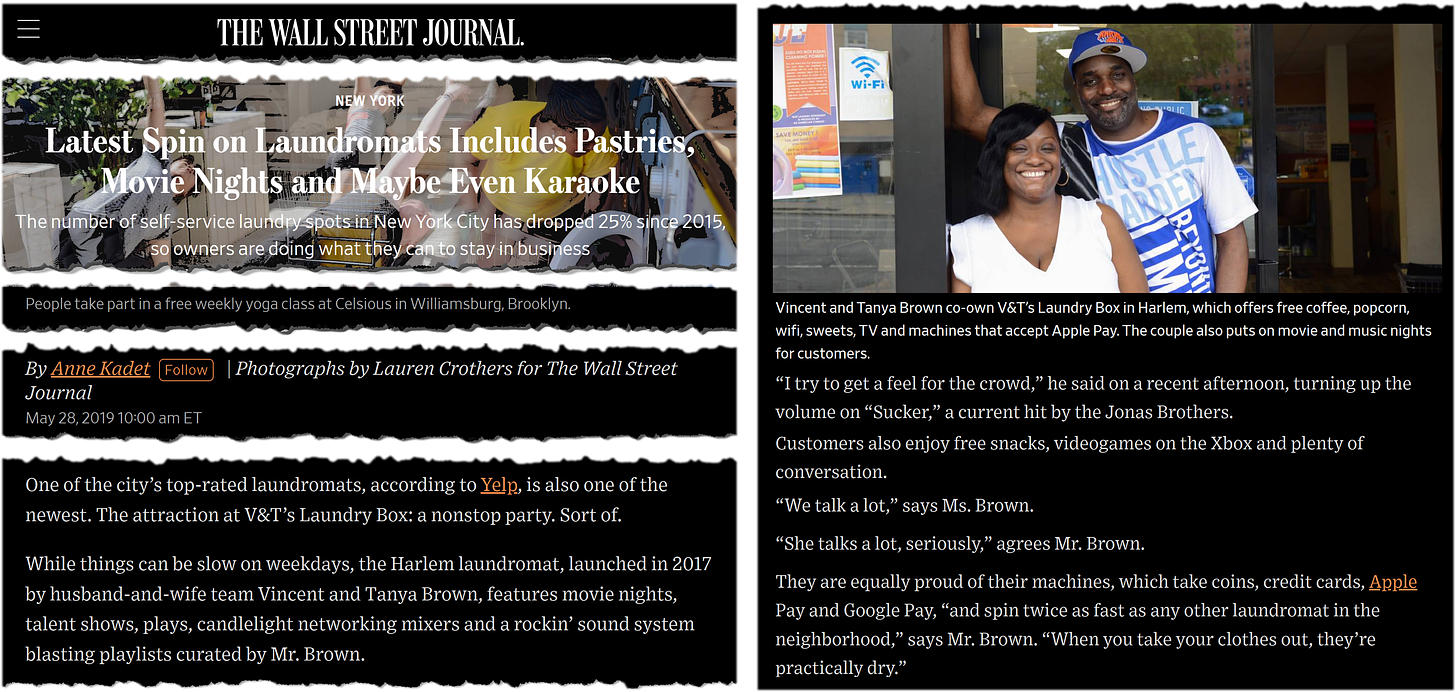

Little Vincent isn’t little anymore. He pushes 6 feet 5 inches and has settled, in love for decades, with his Tanya. Together they own and operate V&T’s Laundry Box in Hamilton Heights in New York City. ‘V’ is for Vincent and ‘T’ for Tanya, of course.

In 2019, V&T’s Laundry Box was profiled in the Wall Street Journal’s Latest Spin on Laundromats Includes Pastries, Movie Nights and Maybe Even Karaoke (free-link; no subscription needed to read article) as one of NYC’s highest rated laundromats according to Yelp.

Vincent Lee and Beverlyn Brown were two class people, part of the underclass. Often drowning in heroin, rarely did they surface for air.

Vincent died early in 1989. Beverlyn, a fiercely loving and troubled woman, OD’d before she turned 30.

Prattled against by a puritanical ethic, bloodied by stigma as stigmata, dependency gripped them as pusillanimous politicians and proselytizing preachers tripped while traipsing “just say no” as THE answer to what ailed my uncle and aunt.

Neither Vincent nor Beverlyn would escape prisons not solely of their own making. Without treatment on demand, they found, in heroin, a costly kind of solace.

“The Lady” smacked hard and claimed each of their lives.

Aunt Jenny and Her Children

On December 17, 1989, three days after her 37th birthday, Vincent’s sister, Virginia Lee—my Aunt Jenny—died in Mother Cabrini Hospital.

Four children survived her: Jamel, Jameak, Janazer, and Katilyn (aka Jamella) with the latter two later dying before either turned 21 years old—Janazer from asthma and Katilyn from AIDS.

The eldest, Jamel Lee, is a security officer with seniority at The Empire State Building. As reported originally on May 3, 2006 and updated in the 2018 online NY Daily News’ article, Tourist Helps Save Empire State Leaper, Jamel, along with a tourist, saved a man who tried to leap from the building’s observation deck.

Earlier this year Jameak Lee, Jenny’s 2nd of four, turned 50 not long after his lower left leg, necrotic, had to be amputated. Family and friends later gathered to celebrate and speak about what he meant to them. In the video below, his brother Jamel and I each share with Jameak how he impacted our lives [I am the first voice, off-camera]. From left to right are Jameak; his son, Justin; and his wife, Lynn. Click here or the thumbnail below to listen.

A Social Worker by Profession

Aunt Jenny, a social worker by profession, worked at being sociable.

She carried herself with the elegance, ease, and confidence of a model, her head never bowed.

She moved with rhythm and grace, upright and self-assured. She never entered your home; she arrived, announcing herself with a broad and generous smile.

From family, it seemed she never expected anything in return.

However, after being laid off as a nurse’s assistant at Bronx Lebanon Hospital, Aunt Jenny became a street worker who was forced to allow her sex to work for her.

I never asked her about this but suspect the circumstances of her life dictated that job chose her.

Most times a night’s work would bring only piddling amounts. Still, this work allowed her to survive and support Jamel, Jameak, and Janazer, her children (Jamella had not yet been born).

When she could no longer find a way to take care of them 365 days of what must have seemed some awfully long years, her mother Pearline, her Aunt Frances, and sometimes my mother, in that extended family kind of way, took care of her children.

From my mother, I learned my Aunt Jenny’s sex work was inventive, ingenious even. She found ways to negotiate through the violence—threatened and real—by men who wanted it the way they wanted it. Not always, but often enough, they got what they wanted.

I was not privy to discussions between Aunt Jenny and her children, my first cousins, Jamel, Jameak, and Janazer (Jamella, aka Katilyn, was a toddler when her mother died) who may or may not have heard rumors about their mother.

I’d like to imagine Aunt Jenny explained the flesh could not always dictate to the soul. That she still fancied herself special—even blessed—in God’s eyes. She bequeathed faith to her children, whose names each begin with “Ja,” a truncated version of “Jah,” which means God (shortened from the Biblical “Yahweh” to “Yah” and then to “Jah”).

Aunt Jenny was not always present in her children’s lives, but, whenever she was, they rarely lacked either for her kindness or that smile.

No Match for HIV

Still, Aunt Jenny would prove no match for HIV, once it was in her system.

In the late 1980’s, this master of guile outsmarted even the shrewdest doctors who were not as sure then, as they are today, the precision with which HIV and its retroviral back-coding intelligence hid itself in the cells of human organs, dormant, and then, jerked by unknown factors, exploded into its host’s bloodstream.

Relentless in its deadly attack on her white blood cells, HIV turned Jenny’s cellular machinery into factories that churned out even more viruses.

Facing certain death, what was a crafty little soul to do to remain dignified in the mind of her children?

Claiming dignity for her children, Aunt Jenny was not one to contemplate suicide as painless. Neither her faith nor her mother would have it.

Though her body withered away, guided by Grandma Pearline, her spirit accepted her God with maddening abandon. At her wake, Aunt Jenny would leave her children praying for more time.

Months after her face first showed the tell-tale pockmarked symptoms—one week before Christmas in the year of her Lord, 1989—Aunt Jenny was taken by the virus.

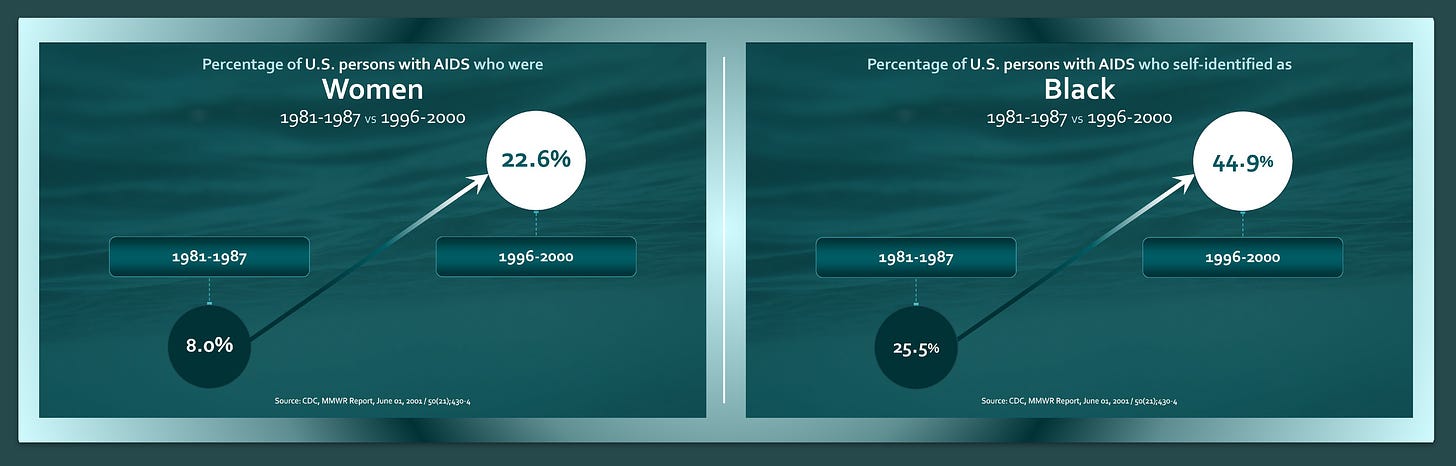

Disparate AIDS Treatment for Jenny (and Other Women)

I say “the virus”—and not “AIDS”—because Aunt Jenny was not diagnosed with AIDS until her final months as her body surrendered both to Pneumocystis carinii and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Women-specific infections taxed her immune system long before pneumonia and cancer captured her soul.

However, in 1989 the Centers for Disease Control predominantly associated AIDS with those opportunistic infections prevalent in male research subjects.

From 1981-1987 only 8% of people with AIDS were women and only 25.5% self-identified as Black (non-Hispanic and Hispanic). In less than 15 years, respectively, those percentages would nearly triple to 22.6% and nearly double to 44.9%.

U.S. government programs would direct AIDS-related benefits disproportionately to White men who were gay, bisexual, or transgender; their gender and race provided an unexpected medical perk.

Aunt Jenny would be denied access to promising medications available in research trials whose criteria favored white gay men.

Be they pregnant or ravaged by vaginal yeast, cervical cancers, and/or excessively bleeding uteri, women would not be as entitled as men were to potentially promising AIDS treatment advancements.

Before her AIDS diagnosis, Jenny was 6’2” and over 150 lbs. Near the end, she weighed less than 100 lbs. as she drifted in and out of sleep. Her head bobbled low and often seemed too heavy for her to lift up.

With her neck stripped of most musculature by the wasting disease associated with AIDS, did her jugular visibly beat the rhythms of her heart, or did I imagine that?

Maybe not in her neck, but I swear that if they wanted, her nurses could see her pulse rather than feel it at her wrist.

Soon morphine became fashionable. With Jenny’s elbow nook bruised, her collapsed veins needled by nurses with morphine, she connected, once more, to the “The Lady” she met on Harlem streets.

Clear of denial and long ago sidetracked by urban alleys, Aunt Jenny’s more acceptable solicitous yet sociable vocation evolved to show the rest of us the way so we could—and would—acknowledge and accept her death.

The Last Meal

On Thanksgiving Day, I arrive late to Bradhurst Avenue in Harlem whose sunlight shades are softened by faint shadows turning sunset orange to gray all around.

I pierce dew-dropped windowpanes with bright falsetto shouts for my grandmother, then hurry past the guttered intercoms and broken mailboxes after finding the building’s front door unlatched.

Pushing past brown walls made bumpy by layered decades of paint, I reckon the elevator is trapped between tenement floors and skim five flights, where Grandma Pearline stands with a smile.

“Toeeeeny, is that you,” she whines, near-sighted and near gone, her voice lilting upward in her North Carolinian way.

I stare past her stomach, pregnant with bulbous growths that should have killed her 10 years before.

But Grandma once told me she’d made a pact with her God that she could remain here on earth until she saw each grandchild grown.

Never could she have imagined that this might mean seeing her own child disappeared from her very own home. Uncle Vincent, her youngest child, had died in her arms in the same room where Aunt Jenny now lay asleep in the bed.

“Hi, Pull-eeen,” I say, aping (as did all my sisters and brothers) my mother’s lifelong mispronunciation, bastardizing Grandma Pearline’s bejeweled name to one that suggests tension.

Butter-skinned by German Dutch, African, and mixed American ancestry, Grandma is pale in the sunlight sifted soft by the pantry’s cheesecloth curtains. I bear hug her, remembering to squeeze gently ‘round that stomach.

When I let go, I feel sad—as though I had just embraced a ghost.

A chill shakes me as I remember one of her youngest grandchildren, Janazer, before long would be grown. Quickly, I pray to her God, “please let her stay.”

With knees knocked by arthritis, in slippers gnarled by bunions, Grandma cooked for hours. She trudged flat-footed from a tiny gas stove to the cracked ivory sink to that ugly ceramic-topped dinner table. Rarely did she rest in the ripped faux leather chairs, circa 1950. It’s the first time I notice Grandma’s kitchen suggests she might be trapped by an era.

Not long before the start of World War II, sometime during the late 1930s and early ’40s, Pearline Head, not yet 20 years old, escaped to The North.

Raised in North Carolina during the Depression, her blue-Black Haitian-Sicilian father, surname Head, and her ivory-White Cherokee and German mother, maiden name Schmarr, were outcast by families, communities, and nations that reviled such unions.

Every now and again I would encourage Grandma to tell me the stories of her childhood. Ever since I was a child with words to speak her name I wanted to know more about where she came from and how she came to be.

But only when I was 23 and revealed I was gay, trusting her to secrets untold, did Pearline cue me about secrets in her past.

That her own father was nearly lynched by White men in Greensboro.

That her own mother had dodged lye hurled by a Black woman she had never before even met who barked: “I’ll make you whiter than white.” Grandma Pearline’s “Momma” was half-White, one-quarter Cherokee, one-quarter Black.

Memories of Aunt Mary first come to me in the 1972 nook of my mind, but they are fleeting. Mary clutched suicide in 1977. Mary and Ola, my mother, were born two years apart, 1942 and 1944, while the distance between my mother and Aunt Jenny is another eight years. Vincent’s birth in 1955 comes three years after Aunt Jenny’s and denotes an era still haunting, ever present, in my grandmother’s kitchen.

The Last Dance

Near dinnertime, Aunt Jenny emerges from the tiny bedroom she shared with her mother, as in childhood, her primary caretaker.

She seems content but weak.

She lugs a tape recorder, an old Panasonic reporter’s model, which she rests atop the television, turning off the football game her eldest son Jamel and I had been enjoying.

Jameak and Janazer, Aunt Jenny’s youngest “Ja’s” at the time—(Jamella/Katilyn was a toddler, already born but given up for adoption and not yet known to the rest of the family)—were with their respective father’s families. (Jameak’s and Jamel’s different fathers passed when both were young; while Janazer’s dad, my Uncle Tyrone, with whom Janazer now lived, had long ago separated from his daughter’s mother).

Slowly, Aunt Jenny turns my way the same moment I rise to greet her.

First, I notice the slight bent in her once statuesque back; suddenly it is obvious her gait labors even more than her mother’s.

She motions to Jamel who deftly interprets the cue, punches “PLAY,” and suddenly there’s music: Marvin’s “Inner-City Blues.”

Aunt Jenny eases closer, then offers her hand. As her arm slips from her oversized robe, it reveals a slippery-skinned skeleton. There is barely flesh to suggest muscles, scarcely muscles thread by tendons, only tendons conspicuously haunting my aunt’s gaunt frame made tired by frail bones.

I am forced to rethink my unspoken muse that her cheeks seem as chiseled and beautiful than ever before.

Stilled by silence and slight in her movement, with nary a word, she hands me this first dance.

Ingenious as ever, Aunt Jenny turns to each one present and repeats the gesture; her sister (my mother) was next, then her mother.

The last dance she saves for her eldest Jamel.

At 19, barely a man, he could not readily see this slow dance was not just his mother’s hello for the evening, but her evensong, which I hold deep in remembrance to honor what she and her brother and her mother endured, not solely for themselves, but also for their own.

Dancin’ With My Sister

by Tony Glover

pansy

my sister

with whom I’ve shared

many things in life

can I get a witness?

dancin’ with my sister

before it’s too late

time to say I love you

my dance no longer waits

pansy?

I love you

more than you’ll ever know

we shared your house

my works

and tonight a dance

hold me tight

never let go

tony

my nephew

pansy’s second yet eldest son

can I get a witness?

dancin’ with my nephew

to marvin’s inner-city blues

cry on my shoulder

if my dance makes you cry

tonight there’s no time to lose

tony?

let go mine and my sister’s pain

and I shall heal you with a dance

your lush voice hushed cannot feign

what your look-away eyes give away

with your hand in mine

I wish I could stay

mommy

my love, an undying source of strength

I have heard, but still need, your witness

dancin’ with my mother

whose love is unconditional and great

still she loses a son

and at least one daughter, maybe more

to a disease that hates love

and promotes hate

mommy?

you know how much I love you

but hate that which kills

first your youngest child

your only son

laying claim to one, maybe both

surviving daughters

threatening to leave you

no first generation

no children

none

makes me wanna holler

the way AIDS do my life

makes me wanna holler

the way AIDS do your life

hang in there, mommy

hang in there

naah nah nah nah

jamel

my eldest son

my first generation

my mother’s second

I have always had your witness

dancin’ with my son

who loves love

and hates hate

your love has helped me survive

a disease that hates love

and promotes hate

jamel?

I love you

don’t you cry too

dry your loving eyes

for though you lose a mother

tonight

my dance with you survives

my dance survives

my mother

my sister

my son

my sister’s second son

tonight

two generations

once

once removed

become closer

become one

together

they will tell my story

how I had to struggle to survive

and how through my dance tonight

in their lives

my love will always be alive

A Tribute in Song: Empty Garden (Hey Hey Johnny)

In the embedded video below, my husband, Charlie sings Empty Garden (Hey, Hey Johnny).

With Bernie Taupin, Elton John composed the song as tribute to John Lennon. Its lyrics capture what comes to mind when we reminisce about family or friends.

What both haunts and comforts us are the kindnesses, large and small, they tendered every day they could as gardener to those who meant the world to them. Once faint, as whispers, what we can remember echoes more deeply.